It’s 2006, and in a dimly lit basement in New Jersey, 18-year-old Dan Rinaldi stands clutching a microphone, his voice echoing off the walls as he auditions for Bedlight for Blue Eyes. “I had just turned 18, driving to our guitarist Derek’s house by myself for the first time,” he recalls. “I went into his basement—it was wild.”

That moment, sparked by a chance MySpace message and a fateful night at CBGB, would thrust him into the pulsing heart of the mid-2000s emo and post-hardcore scene. Nearly two decades later, Dan occupies a different space: a therapist’s office, where the echoes of that era fuel a mission to mend the mental health of the music world he once called home and the people in it.

Dan Joins the Band

Dan’s journey begins in Queens, New York, in an Italian-Catholic household where music was a constant. “I started like any young kid—singing in school plays, choirs,” he says. Theater beckoned in high school, leading him to an arts school near Manhattan. It was there, amid trips to Warped Tour and local gigs, that he stumbled into Bedlight’s orbit. “I saw them play at the Continental in Manhattan,” he says. “Paramore and My American Heart opened—Paramore opened for us, even though I wasn’t in the band yet. I thought, ‘This dude sounds like me.’ It was theater-esque, not like New Found Glory or Taking Back Sunday.”

Months later, a MySpace bulletin announced the band’s singer had departed. Dan auditioned, and the rest was history. “The drummer, Itchy, turned to me and said, ‘Yo, it’s yours if you want it,’” he laughs. “I was like, ‘What are you saying?’ It was super wild.”

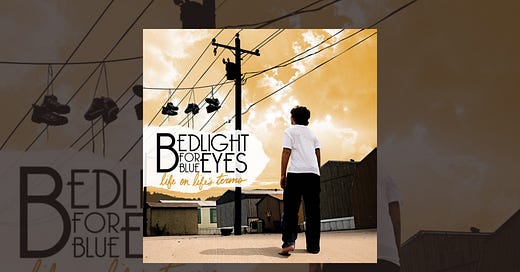

Life On Bedlight’s Terms

What followed was a plunge into the New Jersey scene—a chaotic tapestry of sweaty VFW halls, DIY shows, and a revolving cast of bands like Senses Fail, The Early November, and Tokyo Rose. Signed to Trustkill Records, Bedlight was a rising star, but Dan’s arrival marked a turning point. Their 2007 album, Life on Life’s Terms, ditched The Dawn’s post-hardcore grit for a poppier vibe. “We knew we wanted to break from that post-hardcore sound,” Dan explains. “A lot of The Dawn’s instrumentals came from a hardcore metal band they were in—Sever the Stars or something. But we loved pop—Third Eye Blind, Matchbox 20.” The shift was bold, with early demos on Fruity Loops sounding “like video game music,” he laughed.

Songs like “Waste My Time” and “Ms. Shapes” emerged, polished with producer Tomas Costanza and later Zach and Ken, who’d worked with Mayday Parade and Cartel.

The reception was mixed. “A lot of the original fans were like, ‘What’s this?’” Dan admits. “It took persuading to keep them. The lyrical content, the structures—it was vastly different.” Yet touring broadened their reach, converting fans of bands like All Time Low and Valencia. “We were slowly turning their fans into ours,” he says. “We played more traditional pop, which might’ve stifled our growth in the scene.”

Reflecting on the what-ifs, he muses, “If we’d made Dawn 2.0, we could’ve stayed in that middle ground with Victory or Rise bands. But flipping it gave us a chance—if we’d done a third album, it might’ve pushed us beyond the scene or kept one foot in.”

For Dan, those years were a whirlwind of RAV4 road trips—the car that was practically the official sponsor of —and a brotherhood forged in basements and dive bars. “It surely changed my life,” Dan says. “One minute I thought I was gonna go to college, the next I was on tour.”

But when Bedlight fizzled out, the silence hit hard. “We played our last show months later at School of Rock,” he recalls. “It was depressing. Your life stops in a band—everyone else moves on, and you’re like, ‘Where’d everyone go?’” Encouraged by his then-girlfriend (now wife), he returned to school in his late 20s. “She was like, ‘What are you gonna do?’ I’d dropped out for the band—no degree. I decided, ‘Okay, I can do this as an adult.’”

Finding Your Future Footing

Mental health, a thread from his own struggles, guided him to therapy. “I’ve always had an interest in it—my own mental health too,” he shares. Now in private practice in Massachusetts, Dan sees his past and present converging. “Therapy was a no-brainer,” he says. “How can I find that connection I had in Bedlight? How can I share a conversation without being in a band?” The scene, he notes, was a lifeline for kids wrestling with anxiety and identity—much like his clients today. “A lot of us got into it for that,” he explains, “it’s why it was so great—camaraderie, support.”

Yet he sees a gap: touring musicians lack resources. “We’ve seen what happens when mental health goes unchecked—substance abuse, abuses of power,” he says. Licensing laws confine him to Massachusetts clients, a hurdle he ponders aloud. “If a band’s on a full U.S. tour, I can’t talk to them unless they’re here. It’s wild.” He dreams of a niche practice—perhaps a “Peanuts psychiatry booth” at shows. “Imagine a 15-minute consult for bands or fans,” he says. “A kid being abused at home might feel safe at a show—friends could nudge them to talk.”

Dan’s Instagram, with emo lyric call-outs, already bridges his worlds. “There’s a group of people who grew up with us, never addressed that stuff, and now a new group coming up, trying to find themselves.” A Bedlight reunion? “Touring’s not for me—I couldn’t wave goodbye to my wife and daughter,” he says. “The door’s not closed, but everyone’s moved on. I’d hear a creative pitch—fun shows, not records. What we wrote together was important. I wouldn’t change it without them.”

From basement auditions to therapy sessions, Dan Rinaldi hasn’t strayed far from the scene’s pulse. “I’d love to play music again,” he teases, leaving room for possibility. For now, he’s crafting a new legacy—less about stage lights, more about healing ones, reaching a community that’s always been more than music. “The scene’s better when people are mentally healthy,” he says. “I’ve always advocated for that.”